Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Philippines_(900-1521)

http://www.infoplease.com/country/philippines

http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Philippine_History

http://www.philippinecountry.com/philippine_history

The history of the Philippines (as opposed to its prehistory) is marked by the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI), the first written document found in a Philippine language.

The inscription itself identifies the date of its creation as the year

900. Prior to its discovery in 1989, the earliest record of the

Philippine Islands corresponded with the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. The discovery of the LCI thus extended the record of Philippine history back by 600 years.

After 900, the early history of territories and nation-states prior to

being present-day Philippines is known through archeological findings and records of contacts with other civilizations such as Song Dynasty China and Brunei.

This article covers the history of the Philippines from the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription in 900 AD to the arrival of European explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, which marks the beginning of the Philippine Colonial period (1565-1946).

There are several opposing theories regarding the origins of ancient Filipinos. F. Landa Jocano theorizes that the ancestors of the Filipinos evolved locally. Wilhelm Solheim's Island Origin Theory postulates that the peopling of the archipelago transpired via trade networks originating in the Sundaland area around 48,000 to 5000 BC rather than by wide-scale migration. The Austronesian Expansion Theory states that Malayo-Polynesians coming from Taiwan began migrating to the Philippines around 4000 BC, displacing earlier arrivals.

The Negritos were early settlers, but their appearance in the Philippines has not been reliably dated. They were followed by speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, a branch of the Austronesian languages, who began to arrive in successive waves beginning about 4000 BC, displacing the earlier arrivals. Before the expansion out of Taiwan, recent archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence has linked Austronesian speakers in Insular Southeast Asia to cultures such as the Hemudu and Dapenkeng in Neolithic China.

By 1000 BC the inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago had developed into four distinct kinds of peoples: tribal groups, such as the Aetas, Hanunoo, Ilongots and the Mangyan who depended on hunter-gathering and were concentrated in forests; warrior societies, such as the Isneg and Kalinga who practiced social ranking and ritualized warfare and roamed the plains; the petty plutocracy of the Ifugao Cordillera Highlanders, who occupied the mountain ranges of Luzon; and the harbor principalities of the estuarine civilizations that grew along rivers and seashores while participating in trans-island maritime trade.

Around 300–700 AD the seafaring peoples of the islands traveling in balangays began to trade with the Indianized kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago and the nearby East Asian principalities, adopting influences from both Buddhism and Hinduism

Prehistory

The earliest archeological evidence for man in the archipelago is the 67,000-year-old Callao Man of Cagayan and the Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal, both of whom appear to suggest the presence of human settlement prior to the arrival of the Negritos and Austronesian speaking people.There are several opposing theories regarding the origins of ancient Filipinos. F. Landa Jocano theorizes that the ancestors of the Filipinos evolved locally. Wilhelm Solheim's Island Origin Theory postulates that the peopling of the archipelago transpired via trade networks originating in the Sundaland area around 48,000 to 5000 BC rather than by wide-scale migration. The Austronesian Expansion Theory states that Malayo-Polynesians coming from Taiwan began migrating to the Philippines around 4000 BC, displacing earlier arrivals.

The Negritos were early settlers, but their appearance in the Philippines has not been reliably dated. They were followed by speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, a branch of the Austronesian languages, who began to arrive in successive waves beginning about 4000 BC, displacing the earlier arrivals. Before the expansion out of Taiwan, recent archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence has linked Austronesian speakers in Insular Southeast Asia to cultures such as the Hemudu and Dapenkeng in Neolithic China.

By 1000 BC the inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago had developed into four distinct kinds of peoples: tribal groups, such as the Aetas, Hanunoo, Ilongots and the Mangyan who depended on hunter-gathering and were concentrated in forests; warrior societies, such as the Isneg and Kalinga who practiced social ranking and ritualized warfare and roamed the plains; the petty plutocracy of the Ifugao Cordillera Highlanders, who occupied the mountain ranges of Luzon; and the harbor principalities of the estuarine civilizations that grew along rivers and seashores while participating in trans-island maritime trade.

Around 300–700 AD the seafaring peoples of the islands traveling in balangays began to trade with the Indianized kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago and the nearby East Asian principalities, adopting influences from both Buddhism and Hinduism

Classical States (900 AD to 1535)

Initial recorded history

During the period of the south Indian Pallava dynasty and the north Indian Gupta Empire Indian culture spread to Southeast Asia and the Philippines which led to the establishment of Indianized kingdoms. The end of Philippine prehistory is 900, the date inscribed in the oldest Philippine document found so far, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. From the details of the document, written in Kawi script, the bearer of a debt, Namwaran, along with his children Lady Angkatan and Bukah, are cleared of a debt by the ruler of Tondo. From the various Sanskrit terms and titles seen in the document, the culture and society of Manila Bay was that of a Hindu–Old Malay amalgamation, similar to the cultures of Java, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra at the time. There are no other significant documents from this period of pre-Hispanic Philippine society and culture until the Doctrina Christiana of the late 16th century, written at the start of the Spanish period in both native Baybayin script and Spanish. Other artifacts with Kawi script and baybayin were found, such as an Ivory seal from Butuan dated to the early 11th century and the Calatagan pot with baybayin inscription, dated to the 13th century.In the years leading up to 1000, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous barangays (settlements ranging in size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajahs or sultans or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". States such as the Kingdom of Maynila, the Kingdom of Taytay in Palawan (mentioned by Pigafetta to be where they resupplied when the remaining ships escaped Cebu after Magellan was slain), the Chieftaincy of Coron Island ruled by fierce warriors called Tagbanua as reported by Spanish missionaries mentioned by Nilo S. Ocampo, Namayan, the Dynasty of Tondo, the Confederation of Madyaas, the rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu and the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan. Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription and its context (c. 900AD)

In 1989, Antoon Postma deciphered the text of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription at the National Museum of the Philippines and discovered that it identified the date of its creation as the "Year of Syaka 822, month of Vaisakha." According to Jyotisha (Hindu astronomy),

this corresponded with the year 900 A.D. Prior to the deciphering of

the LCI, Philippine history was traditionally considered to begin at

1521, with the arrival of Magellan and his chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta.

History could not be derived from pre-colonial records because such

records typically did not survive: most of the writing was done on

perishable bamboo or leaves. Because the deciphering of the LCI made it

out to be the earliest written record of the islands that would later

become the Philippines, the LCI reset the traditional boundaries between

Philippine history and prehistory, placing the demarcation line 600

years earlier.

The inscription forgives the descendants of Namwaran from a debt of 926.4 grams of gold, and is granted by the chief of Tondo (an area in Manila) and the authorities of Paila, Binwangan and Pulilan, which are all locations in Luzon. The words are a mixture of Sanskrit, Old Malay, Old Javanese and Old Tagalog.

The subject matter proves that a developed society existed in the

Philippines prior to the Spanish colonization, as well as refuting

earlier claims of the Philippines being a cultural isolate in Asia; the

references to the Chief of Medang Kingdom in Indonesia imply that there were cultural and trade links with empires and territories in other parts of Maritime Southeast Asia, particularly Srivijaya.

Thus, aside from clearly indicating the presence of writing and of

written records at the time, the LCI effectively links the cultural

developments in the Philippines at the time with the growth of a

thalassocratic civilization in Southeast Asia.

The Kingdom of Tondo

Since at least the year 900, the thalassocracy centered in Manila Bay flourished via an active trade with Chinese, Japanese, Malays, and various other peoples in East Asia. Tondo thrived as the capital and the seat of power of this ancient kingdom, which was led by kings under the title "Lakan" and ruled a large part of what is now known as Luzon from or possibly before 900 AD to 1571. During its existence, it grew to become one of the most prominent and wealthy kingdom states in pre-colonial Philippines due to heavy trade and connections with several neighboring nations such as China and Japan. In 900 AD, the lord-minister Jayadewa presented a document of debt forgiveness to Lady Angkatan and her brother Bukah, the children of Namwaran. This is described in the Philippine's oldest known document, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription.

The Rajahnate of Butuan

A golden statuette of the Hindu-Buddhist goddess "Kinari" found in an archeological dig in Esperanza, Agusan del Sur.

The Rajahnate of Cebu

The Rajahnate of Cebu was a classical Philippine state which used to exist on Cebu island prior to the arrival of the Spanish. It was founded by Sri Lumay otherwise known as Rajamuda Lumaya, a minor prince of the Chola dynasty which happened to occupy Sumatra. He was sent by the maharajah to establish a base for expeditionary forces to subdue the local kingdoms but he rebelled and established his own independent Rajahnate instead. This rajahnate warred against the 'magalos' (Slave traders) of Maguindanao and had an alliance with the Butuan Rajahnate before it was weakened by the insurrection of Datu (Lord) Lapulapu.The Confederation of Madja-as

Left to right: [1] Images from the Boxer Codex illustrating an ancient kadatuan or tumao (noble class) Visayan couple, [2] a royal couple of the Visayans and [3] a Visayan princess.

Barangay city-states and Thalassocracy

Since at least the 3rd century, the indigenous peoples were in contact with other Southeast Asian and East Asian nations.

Fragmented ethnic groups established numerous city-states formed by the assimilation of several small political units known as barangay each headed by a Datu, who was then answerable to a Rajah, who headed the city state. Each barangay consisted of about 100 families. Some barangays were big, such as Zubu (Cebu), Butuan, Maktan (Mactan), Irong-Irong (Iloilo), Bigan (Vigan), and Selurong (Manila). Each of these big barangays had a population of more than 2,000.

Even scattered barangays, through the development of inter-island and

international trade, became more culturally homogeneous by the 4th

century. Hindu-Buddhist culture and religion flourished among the noblemen in this era.

By the 9th century, a highly developed society had already established several hierarchies with set professions: The Datu or ruling class, the Maharlika or noblemen, the Timawa or freemen, and the dependent class which is divided into two, the Aliping Namamahay (Serfs) and Aliping Saguiguilid (Slaves).

Many of the barangay were, to varying extents, under the de jure jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Sri Vijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Brunei, Malacca empires, although de facto had established their own independent system of rule. Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Thailand, Java, China, India, Arabia, Japan and the Ryukyu Kingdom flourished during this era. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

In the earliest times, the items which were prized by the people

included jars, which were a symbol of wealth throughout South Asia, and

later metal, salt and tobacco. In exchange, the people would trade

feathers, rhino horn, hornbill beaks, beeswax, birds nests, resin,

rattan.

In the period between the 7th century to the beginning of the 15th

century, numerous prosperous centers of trade had emerged, including the

Kingdom of Namayan which flourished alongside Manila Bay, Cebu, Iloilo, Butuan, the Kingdom of Sanfotsi situated in Pangasinan, the Kingdoms of Zabag and Wak-Wak situated in Pampanga and Aparri (which specialized in trade with Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu in Okinawa).

One example of the use of Baybayin from that time period was found on an earthenware burial jar found in Batangas. Though a common perception is that Baybayin replaced Kawi, many historians believe that they were used alongside each other. Baybayin was noted by the Spanish to be known by everyone, and was generally used for personal and trivial writings. Kawi most likely continued to be used for official documents and writings by the ruling class. Baybayin was simpler and easier to learn, but Kawi was more advanced and better suited for concise writing.

The Emergence of Baybayin and Related Scripts (1200 onwards)

The script used in writing down the LCI is Kawi, which originated in Java, and was used across much of Maritime Southeast Asia. But by at least the 13th century or 14th century, its descendant known in Tagalog as Baybayin was in regular use. The term baybayin literally means syllables, and teh writing system itself is a member of the Brahmic family.

One example of the use of Baybayin from that time period was found on an earthenware burial jar found in Batangas. Though a common perception is that Baybayin replaced Kawi, many historians believe that they were used alongside each other. Baybayin was noted by the Spanish to be known by everyone, and was generally used for personal and trivial writings. Kawi most likely continued to be used for official documents and writings by the ruling class. Baybayin was simpler and easier to learn, but Kawi was more advanced and better suited for concise writing.

Although Kawi came to be replaced by the Latin script,

Baybayin continued to be used during the Spanish colonization of the

Philippines up until the late 19th Century. Closely related scripts

still in use among indigenous peoples today include Hanunóo, Buhid, and Tagbanwa.

Chinese Trade (982 AD onwards)

The earliest date suggested for direct Chinese contact with the Philippines was 982 AD. At the time, merchants from "Ma-i" (now in Mindoro) brought their wares to Guangzhou. This was noted by the Sung Shih (History of the Sung) by Ma Tuan-lin who compiled it with other historical records in the Wen-hsien T’ung-K’ao at the time around the transition between the Sung and Yuan dynasties.

However, actual trade between China and the proto-Philippine states probably started much earlier.

The Country of Mai

Around 1225, the Country of Mai, a Sinified pre-Hispanic Philippine island-state centered in Mindoro,flourished as an entrepot, attracting traders & shipping from the Kingdom of Ryukyu to the Yamato Empire of Japan. Chao Jukua, a customs inspector in Fukien province, China wrote the Zhufan Zhi ("Description of the Barbarous Peoples"), which described trade with this pre-colonial Philippine state.The Sultanate of Lanao

The Sultanates of Lanao in Mindanao, Philippines were founded in the 16th century through the influence of Shariff Kabungsuan, who was enthroned as first Sultan of Maguindanao in 1520. The Maranaos of Lanao were acquainted with the sultanate system when Islam was introduced to the area by Muslim missionaries and traders from the Middle East, Indian and Malay regions who propagated Islam to Sulu and Maguindanao. Unlike in Sulu and Maguindanao, the Sultanate system in Lanao was uniquely decentralized. The area was divided into Four Principalities of Lanao or the Pat a Pangampong a Ranao which are composed of a number of royal houses (Sapolo ago Nem a Panoroganan or The Sixteen (16) Royal Houses) with specific territorial jurisdictions within mainland Mindanao. This decentralized structure of royal power in Lanao was adopted by the founders, and maintained up to the present day, in recognition of the shared power and prestige of the ruling clans in the area, emphasizing the values of unity of the nation (kaiisaisa o bangsa), patronage (kaseselai) and fraternity (kapapagaria).The growth of Islamic Sultanates (1380 onwards)

In 1380, Makhdum Karim, the first Islamic missionary to the Philippines brought Islam to the Archipelago. Subsequent visits of Arab, Malay and Javanese

missionaries helped strengthen the Islamic faith of the Filipinos, most

of whom (except for those in the north) would later become Christian

under the Spanish colonization. The Sultanate of Sulu,

the largest Islamic kingdom in the islands, encompassed parts of

Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. The royal house of the

Sultanate claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad.

Around 1405, the year that the war over succession ended in the Majapahit Empire, Sufi traders introduced Islam into the Hindu-Malayan empires

and for about the next century the southern half of Luzon and the

islands south of it were subject to the various Muslim sultanates of

Borneo. During this period, the Japanese established a trading post at Aparri and maintained a loose sway over northern Luzon.

The Sultanate of Sulu

The official flag of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu under the guidance of Ampun Sultan Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram of Sulu.

Islamic Monarchy

The Islamic sultanates of Sulu and mainland Mindanao represented a

higher stage of political and economic development than the barangay.

These had a feudal form of social organization. Each of them encompassed

more people and wider territory than the barangay. The sultan reigned

supreme over several datus and was conscious of his privilege to rule as

a matter of hereditary "divine right."

Though they presented themselves mainly as administrators of communal

lands, apart from being direct owners of certain lands, the sultans,

datus and the nobility exacted land rent in the form of religious

tribute and lived off the toiling masses. They constituted a landlord

class attended by a retinue of religious teachers, scribes and leading

warriors.

The sultanates emerged in the two centuries precedent to the coming

of Spanish colonialists. They were built up among the so-called third

wave of Malay migrants whose rulers either tried to convert to Islam,

bought out, enslaved or drove away the original non-Muslim inhabitants

of the areas that they chose to settle in. Serfs and slaves alike were

used to till the fields and to make more clearings from the forest.

Throughout the archipelago, the scope of barangays could be enlarged

either through the expansion of agriculture by the toil of the slaves or

serfs, through conquests in war and through interbarangay marriages of

the nobility. The confederations of barangays was usually the result of a

peace pact, a barter agreement or an alliance to fight common internal

and external enemies.

As evident from the forms of social organization already attained,

the precolonial inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago had an

internal basis for further social development. In either barangay or

sultanate, there was a certain mode of production which was bound to

develop further until it would wear out and be replaced with a new one.

There were definite classes whose struggle was bound to bring about

social development. As a matter of fact, the class struggle within the

barangay was already getting extended into interbarangay wars.

The

barangay was akin to the Greek city-state in many respects and the

sultanate to the feudal commonwealth of other countries.

The people had developed extensive agricultural fields. In the plains

or in the mountains, the people had developed irrigation systems. The

Ifugao rice terraces were the product of the engineering genius of the

people; a marvel of 12,000 miles if strung end-to-end. There were

livestock-raising, fishing and brewing of beverages. Also there were

mining, the manufacture of metal implements, weapons and ornaments,

lumbering, shipbuilding and weaving. The handicrafts were developing

fast. Gunpowder had also come into use in warfare. As far north as

Manila, when the Spaniards came, there was already a Muslim community

which had cannons in its weaponry.

The ruling classes made use of arms to maintain the social system, to

assert their independence from other barangays or to repel foreign

invaders. Their jurisprudence would still be borne out today by the

so-called Code of Kalantiyaw and the Muslim laws. These were touchstones

of their culture. There was a written literature which included epics,

ballads, riddles and verse-sayings; various forms and instruments of

music and dances; and art works that included well-designed bells,

drums, gongs, shields, weapons, tools, utensils, boats, combs, smoking

pipes, lime tubes and baskets. The people sculpted images from wood,

bone, ivory, horn or metals. In areas where anito worship and polytheism

prevailed, the images of flora and fauna were imitated, and in the

areas where the Muslim faith prevailed, geometric and arabesque designs

were made. Morga's Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, a record of what the

Spanish conquistadores came upon, would later be used by Dr. Jose Rizal

as testimony to the achievement of the indios in precolonial times.

There was interisland commerce ranging from Luzon to Mindanao and

vice-versa. There were extensive trade relations with neighboring

countries like China, Indochina, North Borneo, Indonesia, Malaya, Japan

and Thailand. Traders from as far as India and the Middle East vied for

commerce with the precolonial inhabitants of the archipelago. As early

as the 9th century, Sulu was an important trading emporium where trading

ships from Cambodia, China and Indonesia converged. Arab traders

brought goods from Sulu to the Chinese mainland through the port of

Canton. In the 14th century, a large fleet of 60 vessels from China

anchored at Manila Bay, Mindoro and Sulu. Previous to this, Chinese

trading junks had been intermittently sailing into various points of the

Philippine shoreline. The barter system was employed or gold and metal

gongs were used as medium of exchange.

Expansion of Trade (1st Century - 14th Century AD)

Jocano refers to the time between the 1st and 14th Century AD as the Philippines' emergent phase.

It was characterized by intensive trading, and saw the rise of

definable social organization, and, among the more progressive

communities, the rise of certain dominant cultural patterns. The

advancements that brought this period were made possible by the

increased use of iron tools, which allowed such stable patterns to form.

This era also saw the development of writing. The first surviving

written artifact from the Philippines, now known as the Laguna

Copperplate Inscription, was written in 900 AD, marking the end of what

is considered Philippine prehistory and heralding the earliest phase

of Philippine history - that of the time between the first written

artifact in 900 AD and the arrival of colonial powers in 1521.

Attack by Sultanate of Brunei (1500 A.D.)

Around the year 1500 AD, the Kingdom of Brunei under Sultan Bolkiah attacked the kingdom of Tondo and established a city with the Malay name of Selurong (later to become the city of Maynila) on the opposite bank of Pasig River. The traditional Rajahs of Tondo, the Lakandula, retained their titles and property but the real political power came to reside in the House of Soliman, the Rajahs of Manila.

The Sultanate of Maguindanao

At the end of the 15th century, Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan of Johor introduced Islam in the island of Mindanao and he subsequently married Paramisuli, an Iranun Princess from Mindanao, and established the Sultanate of Maguindanao. By the 16th century, Islam had spread to other parts of the Visayas and Luzon.The expansion of Islam

Spanish settlement and rule (1565–1898)

Early Spanish expeditions and conquests

Over the next several decades, other Spanish expeditions were dispatched to the islands. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition to the islands and gave the name Las Islas Filipinas (after Philip II of Spain) to the islands of Samar and Leyte. The name was then extended to the entire archipelago later on in the Spanish era.

A late 17th-century manuscript by Gaspar de San Agustin from the Archive of the Indies, depicting López de Legazpi's conquest of the Philippines

Legazpi built a fort in Maynila and made overtures of friendship to Lakan Dula, Rajah of Tondo, who accepted. However, Maynila's former ruler, Rajah Sulayman, refused to submit to Legazpi, but failed to get the support of Lakandula or of the Pampangan and Pangasinan settlements to the north. When Sulaiman and a force of Filipino warriors attacked the Spaniards in the battle of Bangcusay, he was finally defeated and killed.

In 1587, Magat Salamat, one of the children of Lakan Dula, along with Lakan Dula's nephew and lords of the neighbouring areas of Tondo, Pandacan, Marikina, Candaba, Navotas and Bulacan, were executed when the Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588 failed in which a planned grand alliance with the Japanese admiral Gayo, Butuan's last rajah and Brunei's Sultan Bolkieh, would have restored the old aristocracy. Its failure resulted in the hanging of Agustín de Legazpi (great grandson of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi and the initiator of the plot) and the execution of Magat Salamat (the crown-prince of Tondo).

Spanish power was further consolidated after Miguel López de Legazpi's conquest of the Confederation of Madya-as, his subjugation of Rajah Tupas, the King of Cebu and Juan de Salcedo's conquest of the provinces of Zambales, La Union, Ilocos, the coast of Cagayan, and the ransacking of the Chinese warlord Limahong's pirate kingdom in Pangasinan.

The Spanish and the Moros also waged many wars over hundreds of years in the Spanish-Moro Conflict, not until the 19th century did Spain succeed in defeating the Sulu Sultanate and taking Mindanao under nominal suzerainty.

Spanish settlement during the 16th and 17th centuries

The "Memoria de las Encomiendas en las Islas" of 1591, just twenty years after the conquest of Luzon, reveals a remarkable progress in the work of colonization and the spread of Christianity. A cathedral was built in the city of Manila with an episcopal palace, Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan monasteries and a Jesuit house. The king maintained a hospital for the Spanish settlers and there was another hospital for the natives run by the Franciscans. The garrison was composed of roughly two hundred soldiers. In the suburb of Tondo there was a convent run by Franciscan friars and another by the Dominicans that offered Christian education to the Chinese converted to Christianity. The same report reveals that in and around Manila were collected 9,410 tributes, indicating a population of about 30,640 who were under the instruction of thirteen missionaries (ministers of doctrine), apart from the monks in monasteries. In the former province of Pampanga the population estimate was 74,700 and 28 missionaries. In Pangasinan 2,400 people with eight missionaries. In Cagayan and islands Babuyanes 96,000 people but no missionaries. In La Laguna 48,400 people with 27 missionaries. In Bicol and Camarines Catanduanes islands 86,640 people with fifteen missionaries. The total was 667,612 people under the care of 140 missionaries, of which 79 were Augustinians, nine Dominicans and 42 Franciscans.The fragmented nature of the islands made it easy for Spanish colonization. The Spanish then brought political unification to most of the Philippine archipelago via the conquest of the various states although they were unable to fully incorporate parts of the sultanates of Mindanao and the areas where tribes and highland plutocracy of the Ifugao of Northern Luzon were established. The Spanish introduced elements of western civilization such as the code of law, western printing and the Gregorian calendar alongside new food resources such as maize, pineapple and chocolate from Latin America.

Outside the tertiary institutions, the efforts of missionaries were in no way limited to religious instruction but also geared towards promoting social and economic advancement of the islands. They cultivated into the natives their innate taste for music and taught Spanish language to children. They also introduced advances in rice agriculture, brought from America corn and cocoa and developed the farming of indigo, coffee and sugar cane. The only commercial plant introduced by a government agency was the plant of tobacco.

Church and state were inseparably linked in Spanish policy, with the state assuming responsibility for religious establishments. One of Spain's objectives in colonizing the Philippines was the conversion of the local population to Roman Catholicism. The work of conversion was facilitated by the absence of other organized religions, except for Islam, which was still predominant in the southwest. The pageantry of the church had a wide appeal, reinforced by the incorporation of indigenous social customs into religious observances. The eventual outcome was a new Roman Catholic majority, from which the Muslims of western Mindanao and the upland tribal peoples of Luzon remained detached and alienated (such as the Ifugaos of the Cordillera region and the Mangyans of Mindoro).

At the lower levels of administration, the Spanish built on traditional village organization by co-opting local leaders. This system of indirect rule helped create an indigenous upper class, called the principalía, who had local wealth, high status, and other privileges. This perpetuated an oligarchic system of local control. Among the most significant changes under Spanish rule was that the indigenous idea of communal use and ownership of land was replaced with the concept of private ownership and the conferring of titles on members of the principalia.

Around 1608 William Adams, an English navigator contacted the interim governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who wished to establish direct trade contacts with New Spain. Friendly letters were exchanged, officially starting relations between Japan and New Spain. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from Mexico, via the Royal Audiencia of Manila, and administered directly from Spain from 1821 after the Mexican revolution, until 1898.

Many of the Aztec and Mayan warriors that López de Legazpi brought with him eventually settled in Mexico, Pampanga where traces of Aztec and Mayan influence can still be found in the many chico plantations in the area (chico is a fruit indigenous only to Mexico) and also by the name of the province itself.

The Manila galleons which linked Manila to Acapulco traveled once or twice a year between the 16th and 19th centuries. The Spanish military fought off various indigenous revolts and several external colonial challenges, especially from the British, Chinese pirates, Dutch, and Portuguese. Roman Catholic missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity and founded schools, universities, and hospitals. In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced education, establishing public schooling in Spanish.

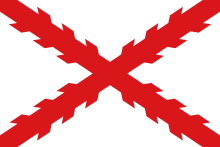

Coat of arms of Manila were at the corners of the Cross of Burgundy in the Spanish-Filipino battle standard.

Spanish rule during the 18th century

Colonial income derived mainly from entrepôt trade: The Manila Galleons sailing from the Fort of Manila to the Fort of Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico brought shipments of silver bullion, and minted coin that were exchanged for return cargoes of Asian, and Pacific products. A total of 110 Manila galleons set sail in the 250 years of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade (1565 to 1815). There was no direct trade with Spain until 1766.The Philippines was never profitable as a colony during Spanish rule, and the long war against the Dutch in the 17th century together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury. The Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain, in which he advises to abandon the colony.

The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown, and the 200-year-old fortifications at Manila had not been improved much since first built by the early Spanish colonizers. This was one of the circumstances that made possible the brief British occupation of Manila between 1762 and 1764.

British invasion (1762–1764)

The British forces were confined to Manila and the nearby port of Cavite by the resistance organised by the provisional Spanish colonial government. Suffering a breakdown of command and troop desertions as a result of their failure to secure control of the Philippines, the British ended their occupation of Manila by sailing away in April 1764 as agreed to in the peace negotiations in Europe. The Spaniards then persecuted the Binondo Chinese community for its role in aiding the British.

Spanish rule in the second part of the 18th century

In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas established the Economic Society of the Friends of the Country. The Philippines was administered from the Viceroyalty of New Spain until the grant of independence to Mexico in 1821 necessitated the direct rule from Spain of the Philippines from that year.

Spanish rule during the 19th century

During the 19th century Spain invested heavily in education and infrastructure. Through the Education Decree of December 20, 1863, Queen Isabella II of Spain decreed the establishment of a free public school system that used Spanish as the language of instruction, leading to increasing numbers of educated Filipinos. Additionally, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut travel time to Spain, which facilitated the rise of the ilustrados, an enlightened class of Filipinos that had been able to expand their studies in Spain and Europe.Spanish Manila was seen in the 19th century as a model of colonial governance that effectively put the interests of the original inhabitants of the islands before those of the colonial power. As John Crawfurd put it in its History of the Indian Archipelago, in all of Asia the "Philippines alone did improve in civilization, wealth, and populousness under the colonial rule" of a foreign power. John Bowring, Governor General of British Hong Kong from 1856 to 1860, wrote after his trip to Manila:

"Credit is certainly due to Spain for having bettered the condition of a people who, though comparatively highly civilized, yet being continually distracted by petty wars, had sunk into a disordered and uncultivated state.

The inhabitants of these beautiful Islands upon the whole, may well be considered to have lived as comfortably during the last hundred years, protected from all external enemies and governed by mild laws vis-a-vis those from any other tropical country under native or European sway, owing in some measure, to the frequently discussed peculiar (Spanish) circumstances which protect the interests of the natives.

The inhabitants of the Philippines, Frederick Henry Sawyer wrote: "Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased. Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives can compare with the Philippines as they were until 1895?."

The first official census in the Philippines was carried out in 1878. The colony's population as of December 31, 1877, was recorded at 5,567,685 persons.[92] This was followed by the 1887 census that yielded a count of 6,984,727, while that of 1898 yielded 7,832,719 inhabitants .

The estimated GDP per capita for the Philippines in 1900, the year Spain left, was of $1,033.00. That made it the second richest place in all of Asia, just a little behind Japan ($1,135.00), and far ahead of China ($652.00) or India ($625.00).

____________________________________________

Contrary to popular belief, the so-called “Spanish period” in Philippine history does not begin with Magellan’s arrival in Cebu and his well-deserved death in the Battle of Mactan in 1521. Magellan may have planted a cross and left the Santo Niño with the wife of Humabon, but that is not a real “conquista” [conquest]. The Spanish dominion over the islands to be known as “Filipinas” began only in 1565, with the arrival of Legazpi. From Cebu, Legazpi moved to other populated and, we presume, important native settlements like Panay and later Maynila (some thought the name was Maynilad because of the presence of Mangrove Trees in the area called nilad).

| When | Who | Ship(s) | Where |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1521 | Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepcion, Santiago and Victoria | Visayas (Eastern Samar, Homonhon, Limasawa, Cebu) | |

| 1525 | Santa María de la Victoria, Espiritu Santo, Anunciada, San Gabriel, Santa María del Parral, San Lesmes and Santiago | Surigao, Islands of Visayas and Mindanao | |

| 1526 | 4 unknown ships | Sighted land near Philippines, Landed on Moluccas | |

| 1527 | 3 unknown ships | Mindanao | |

| 1542 | Santiago, Jorge, San Antonio, San Cristóbal, San Martín, and San Juan | Visayas (Eastern Samar, Leyte), Mindanao (Saranggani) | |

| 1564 | San Pedro, San Pablo, San Juan and San Lucas | Almost entire Philippines |

Primary Sources for Early Philippine History

Primary sources for this period in Philippine history are sparse, which explains why so little is known. It is however, postulated that during the more than 300 years of Spain's colonization, Spanish authorities in the Philippine had successfully cleared through burning or burying written records and other documentaries that would establish proof of governance on the various existing small kingdoms and sultanates they subdued. This is evidenced by the Laguna Copperplate Inscription written in copper metal sheet. The inscription writing in Kawi script manifest the existence of a developed writing system and government structure prior to the arrival of Spaniards and its subsequent establishment of Spanish colonies.

The LCI is both the earliest local source on this era and the earliest primary source, with the Calatagan jar being more or less contemporary, although the translation of the text on the jar is in some question. Early contacts with Japan, China, and by Muslim traders produced the next set of primary sources. Genealogical records by Muslim Filipinos who trace their family roots to this era constitute the next set of sources. Another short primary source concerns the attack by Brunei's king Bolkiah on Manila Bay in 1500. Finally, and perhaps with the most detail, Spanish chroniclers in the 17th century collected accounts and histories of that time, putting into writing the remembered history of the later part of this era, and noting the then-extant cultural patterns which at that time had not yet been swept away by the coming tide of hispanization.

The social and political organization of the population in the widely scattered islands evolved into a generally common pattern. Only the permanent-field rice farmers of northern Luzon had any notion of territoriality. The basic unit of settlement was the barangay, formerly a kinship group headed by a datu (chief). Within the barangay (Malay term for boat; also came to be used for the communal settlements established by migrants who came from the Indonesian archipelago and elsewhere. The term replaces the word barrio, formerly used to identify the lowest political subdivision in the Philippines),

the broad social divisions consisted of nobles, including the datu;

freemen; and a group described before the Spanish period as dependents.

Dependents included several categories with differing status: landless agricultural workers; those who had lost freeman status because of indebtedness or punishment for crime; and slaves, most of whom appear to have been war captives.

In the 14th century

Arab traders from Malay and Borneo introduced Islam into the southern

islands and extended their influence as far north as Luzon. Islam was

brought to the Philippines by traders and proselytizers from the

Indonesian islands. By the 16th century, Islam was recognized in the

Sulu Archipelago and spread from there to Mindanao; it had reached the

Manila area by 1565.

The

first Europeans to visit (1521) the Philippines were those in the

Spanish expedition around the world headed by the Portuguese explorer

Ferdinand Magellan. Other Spanish

expeditions followed, including one from New Spain (Mexico) under López

de Villalobos, who in 1542 named the islands for the infante Philip,

later Philip II. Muslim immigrants introduced a political concept of

territorial states ruled by rajas or sultans who exercised suzerainty

over the datu. Neither the political state concept of the Muslim rulers

nor the limited territorial concept of the inactive rice farmers of

Luzon, however, spread beyond the areas where they originated. The

majority of the estimated 500,000 people in the islands lived in barangay settlements when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century.

Geography

The Philippine islands are an archipelago of over 7,000 islands lying

about 500 mi (805 km) off the southeast coast of Asia. The overall land

area is comparable to that of Arizona. Only about 7% of the islands are

larger than one square mile, and only one-third have names. The largest

are Luzon in the north (40,420 sq mi; 104,687 sq km), Mindanao in the

south (36,537 sq mi; 94,631 sq km), and Visayas (23,582 sq mi; 61,077 sq km).

The islands are of volcanic origin, with the larger ones crossed by

mountain ranges. The highest peak is Mount Apo (9,690 ft; 2,954 m) on

Mindanao.

Government

Republic. Democratic (The Philippines has the oldest Democratic system of government in South-East Asia).

Philippine History/Before The Coming of Spanish Colonialists

Before

the coming of Spanish colonizers, the people of the Philippine

archipelago had already attained a semicommunal and semislave social

system in many parts and also a feudal system in certain parts,

especially in Mindanao and Sulu, where such a feudal faith as Islam had

already taken roots. The Aetas had the lowest form of social

organization, which was primitive communal.

The Society

The barangay was the typical community in the whole archipelago. It was the basic political and economic unit independent of similar others. Each embraced a few hundreds of people and a small territory. Each was headed by a chieftain called the rajah or datu.

Social Structure

The social structure comprised a petty nobility, the ruling class

which had started to accumulate land that it owned privately or

administered in the name of the clan or community.

- Maharlika (Datu in Visayas): an intermediate class of freemen called the Maharlika who had enough land for their livelihood or who rendered special service to the rulers and who did not have to work in the fields.

- Timawa: the ruled classes that included the timawa, the serfs who shared the crops with the petty nobility.

- Alipin (Oripun in Visayas): and also the slaves and semislaves who worked without having any definite share in the harvest. There were two kinds of slaves then: those who had their own quarters, the aliping namamahay (aliping mamahay in Visayas), and those who lived in their master's house, the aliping sagigilid (aliping hayohay in Visayas). One acquired the status of a serf or a slave by inheritance, failure to pay debts and tribute, commission of crimes and captivity in wars between barangays.

History

The Philippines' aboriginal inhabitants arrived from the Asian mainland

around 25,000

BC

They were followed by waves

of Indonesian and Malayan settlers from 3000

BC

onward. By the 14th century

AD

, extensive trade was being conducted with India,

Indonesia, China, and Japan.

Ferdinand Magellan, the Portuguese navigator in the service of Spain,

explored the Philippines in 1521. Twenty-one years later, a Spanish

exploration party named the group of islands in honor of Prince Philip,

who was later to become Philip II of Spain. Spain retained possession of

the islands for the next 350 years.

The Philippines were ceded to the U.S. in 1899 by the Treaty of Paris

after the Spanish-American War. Meanwhile, the Filipinos, led by Emilio

Aguinaldo, had declared their independence. They initiated guerrilla

warfare against U.S. troops that persisted until Aguinaldo's capture in

1901. By 1902, peace was established except among the Islamic Moros on the

southern island of Mindanao.

The first U.S. civilian governor-general was William Howard Taft

(1901–1904). The Jones Law (1916) established a Philippine

legislature composed of an elective Senate and House of Representatives.

The Tydings-McDuffie Act (1934) provided for a transitional period until

1946, at which time the Philippines would become completely independent.

Under a constitution approved by the people of the Philippines in 1935,

the Commonwealth of the Philippines came into being with Manuel Quezon y

Molina as president.

On Dec. 8, 1941, the islands were invaded by Japanese troops. Following

the fall of Gen. Douglas MacArthur's forces at Bataan and Corregidor,

Quezon instituted a government-in-exile that he headed until his death in

1944. He was succeeded by Vice President Sergio Osmeña. U.S. forces

under MacArthur reinvaded the Philippines in Oct. 1944 and, after the

liberation of Manila in Feb. 1945, Osmeña reestablished the

government.

Philippine History/The Spanish Conquest

The

Spanish Conquest was the result of the Age of Exploration when

Europeans explored distant seas in finding new lands to conquer as well

as a new route to the Spice Islands or Moluccas in Indonesia.

Spanish Colonization (1521 - 1898)

Early Spanish expeditions

Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines in 1521.

The Philippine islands first came to the attention of Europeans with the Spanish expedition around the world led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Magellan landed on the island of Cebu, claiming the lands for Spain and naming them Islas de San Lazaro. He set up friendly relations with some of the local chieftains and converted some of them to Roman Catholicism. However, Magellan was killed by natives, led by a local chief named Lapu-Lapu, who go up against foreign domination.

Over the next several decades, other Spanish expeditions were send off to the islands. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition to the islands and gave the name Las Islas Filipinas (after Philip II of Spain) to the islands of Samar and Leyte. The name would later be given to the entire archipelago.

The Philippine islands first came to the attention of Europeans with the Spanish expedition around the world led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Magellan landed on the island of Cebu, claiming the lands for Spain and naming them Islas de San Lazaro. He set up friendly relations with some of the local chieftains and converted some of them to Roman Catholicism. However, Magellan was killed by natives, led by a local chief named Lapu-Lapu, who go up against foreign domination.

Over the next several decades, other Spanish expeditions were send off to the islands. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition to the islands and gave the name Las Islas Filipinas (after Philip II of Spain) to the islands of Samar and Leyte. The name would later be given to the entire archipelago.

The invasion of the

Filipinos by Spain did not begin in earnest until 1564, when another

expedition from New Spain, commanded by Miguel López de Legaspi,

arrived. Permanent Spanish settlement

was not established until 1565 when an expedition led by Miguel López

de Legazpi, the first Governor-General of the Philippines, arrived in

Cebu from New Spain. Spanish leadership was soon established over many

small independent communities that previously had known no central rule.

Six years later, following the defeat of the local Muslim ruler,

Legazpi established a capital at Manila, a location that offered the

outstanding harbor of Manila Bay, a large population, and closeness to

the sufficient food supplies of the central Luzon rice lands. Manila

became the center of Spanish civil, military, religious, and commercial

activity in the islands. By 1571, when López de Legaspi established the

Spanish city of Manila on the site of a Moro town he had conquered the

year before, the Spanish grip in the Philippines was secure which became

their outpost in the East Indies, in spite of the opposition

of the Portuguese, who desired to maintain their monopoly on East Asian

trade. The Philippines was administered as a province of New Spain

(Mexico) until Mexican independence (1821).

Manila revolted the

attack of the Chinese pirate Limahong in 1574. For centuries before the

Spanish arrived the Chinese had traded with the Filipinos, but evidently

none had settled permanently in the islands until after the conquest.

Chinese trade and labor were of great importance in the early development

of the Spanish colony, but the Chinese came to be feared and hated

because of their increasing numbers, and in 1603 the Spanish murdered

thousands of them (later, there were lesser massacres of the Chinese).

The Spanish governor,

made a viceroy in 1589, ruled with the counsel of the powerful royal

audiencia. There were frequent uprisings by the Filipinos, who disliked

the encomienda system. By the end of the 16th cent. Manila had become a

leading commercial center of East Asia, carrying on a prosperous trade

with China, India, and the East Indies. The Philippines supplied some

wealth (including gold) to Spain, and the richly loaded galleons plying

between the islands and New Spain were often attacked by English

freebooters. There was also trouble from other quarters, and the period

from 1600 to 1663 was marked by continual wars with the Dutch, who were

laying the foundations of their rich empire in the East Indies, and with

Moro pirates. One of the most difficult problems the Spanish faced was

the defeat of the Moros. Irregular campaigns were conducted against them

but without conclusive results until the middle of the 19th century. As

the power of the Spanish Empire diminished, the Jesuit orders became

more influential in the Philippines and obtained great amounts of

property.

Occupation of the

islands was accomplished with relatively little bloodshed, partly

because most of the population (except the Muslims) offered little armed

battle initially. A significant problem the Spanish faced was the

invasion of the Muslims of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. The

Muslims, in response to attacks on them from the Spanish and their

native allies, raided areas of Luzon and the Visayas that were under

Spanish colonial control. The Spanish conducted intermittent military

campaigns against the Muslims, but without conclusive results until the

middle of the 19th century.

Church and state were

inseparably linked in Spanish policy, with the state assuming

responsibility for religious establishments. One of Spain's objectives

in colonizing the Philippines was the conversion of Filipinos to

Catholicism. The work of conversion was facilitated by the absence of

other organized religions, except for Islam, which predominated in the

south. The pageantry of the church had a wide plea, reinforced by the

incorporation of Filipino social customs into religious observances. The

eventual outcome was a new Christian majority of the main Malay lowland

population, from which the Muslims of Mindanao and the upland tribal

peoples of Luzon remained detached and separated.

At the lower levels

of administration, the Spanish built on traditional village organization

by co-opting local leaders. This system of indirect rule helped create

in a Filipino upper class, called the principalía, who had local wealth,

high status, and other privileges. This achieved an oligarchic system

of local control. Among the most significant changes under Spanish rule

was that the Filipino idea of public use and ownership of land was

replaced with the concept of private ownership and the granting of

titles on members of the principalía.

The Philippines was

not profitable as a colony, and a long war with the Dutch in the 17th

century and intermittent conflict with the Muslims nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury. Colonial income derived mainly from entrepôt trade: The Manila Galleons sailing from Acapulco on the west coast

of Mexico brought shipments of silver bullion and minted coin that were

exchanged for return cargoes of Chinese goods. There was no direct

trade with Spain.

Decline of Spanish rule

Spanish

rule on the Philippines was briefly interrupted in 1762, when British

troops invaded and occupied the islands as a result of Spain's entry

into the Seven Years' War. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 brought back

Spanish rule and the British left in 1764. The brief British occupation

weakened Spain's grip on power and sparked rebellions and demands for

independence.

In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas founded the Economic Society of Friends of the Country. The Philippines by this time was administered directly from Spain. Developments in and out of the country helped to bring new ideas to the Philippines. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut travel time to Spain. This prompted the rise of the ilustrados, an enlightened Filipino upper class, since many young Filipinos were able to study in Europe.

Enlightened by the Propaganda Movement to the injustices of the Spanish colonial government and the "frailocracy", the ilustrados originally clamored for adequate representation to the Spanish Cortes and later for independence. José Rizal, the most celebrated intellectual and essential illustrado of the era, wrote the novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, which greatly inspired the movement for independence. The Katipunan, a secret society whose primary principle was that of overthrowing Spanish rule in the Philippines, was founded by Andrés Bonifacio who became its Supremo (leader).

The Philippine Revolution began in 1896. Rizal was concerned in the outbreak of the revolution and executed for treason in 1896. The Katipunan split into two groups, Magdiwang led by Andrés Bonifacio and Magdalo led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Conflict between the two revolutionary leaders ended in the execution or assassination of Bonifacio by Aguinaldo's soldiers. Aguinaldo agreed to a treaty with the Pact of Biak na Bato and Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries were exiled to Hong Kong.

It was the opposition to the power of the clergy that in large measure brought about the rising attitude for independence. Spanish injustices, prejudice, and economic oppressions fed the movement, which was greatly inspired by the brilliant writings of José Rizal. In 1896 revolution began in the province of Cavite, and after the execution of Rizal that December, it spread throughout the major islands. The Filipino leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, achieved considerable success before a peace was patched up with Spain. The peace was short-lived, however, for neither side honored its agreements, and a new revolution was made when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898.

The Spanish-American war started in 1898 after the USS Maine, sent to Cuba in connection with an attempt to arrange a peaceful resolution between Cuban independence ambitions and Spanish colonialism, was sunk in Havana harbor. After the U.S. naval victory led by Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish squadron at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, the U.S. invited Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines, which he did on May 19, 1898, in the hope he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government. By the time U.S. land forces had arrived, the Filipinos had taken control of the entire island of Luzon, except for the walled city of Intramuros Manila, which they were besieging. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines in Kawit, Cavite, establishing the First Philippine Republic under Asia's first democratic constitution. Their dreams of independence were crushed when the Philippines were transferred from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1898), which closed the Spanish-American War.

Concurrently, a German squadron under Admiral Diedrichs arrived in Manila and declared that if the United States did not grab the Philippines as a colonial possession, Germany would. Since Spain and the U.S. ignored the Filipino representative, Felipe Agoncillo, during their negotiations in the Treaty of Paris, the Battle of Manila between Spain and the U.S. was alleged by some to be an attempt to exclude the Filipinos from the eventual occupation of Manila. Although there was substantial domestic opposition, the United States decided neither to return the Philippines to Spain, nor to allow Germany to take over the Philippines. Therefore, in addition to Guam and Puerto Rico, Spain was forced in the negotiations to hand over the Philippines to the U.S. in exchange for US$20,000,000.00, which the U.S. later claimed to be a "gift" from Spain. The first Philippine Republic rebelled against the U.S. occupation, resulting in the Philippine-American War (1899–1913).

In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas founded the Economic Society of Friends of the Country. The Philippines by this time was administered directly from Spain. Developments in and out of the country helped to bring new ideas to the Philippines. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut travel time to Spain. This prompted the rise of the ilustrados, an enlightened Filipino upper class, since many young Filipinos were able to study in Europe.

Enlightened by the Propaganda Movement to the injustices of the Spanish colonial government and the "frailocracy", the ilustrados originally clamored for adequate representation to the Spanish Cortes and later for independence. José Rizal, the most celebrated intellectual and essential illustrado of the era, wrote the novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, which greatly inspired the movement for independence. The Katipunan, a secret society whose primary principle was that of overthrowing Spanish rule in the Philippines, was founded by Andrés Bonifacio who became its Supremo (leader).

The Philippine Revolution began in 1896. Rizal was concerned in the outbreak of the revolution and executed for treason in 1896. The Katipunan split into two groups, Magdiwang led by Andrés Bonifacio and Magdalo led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Conflict between the two revolutionary leaders ended in the execution or assassination of Bonifacio by Aguinaldo's soldiers. Aguinaldo agreed to a treaty with the Pact of Biak na Bato and Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries were exiled to Hong Kong.

It was the opposition to the power of the clergy that in large measure brought about the rising attitude for independence. Spanish injustices, prejudice, and economic oppressions fed the movement, which was greatly inspired by the brilliant writings of José Rizal. In 1896 revolution began in the province of Cavite, and after the execution of Rizal that December, it spread throughout the major islands. The Filipino leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, achieved considerable success before a peace was patched up with Spain. The peace was short-lived, however, for neither side honored its agreements, and a new revolution was made when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898.

The Spanish-American war started in 1898 after the USS Maine, sent to Cuba in connection with an attempt to arrange a peaceful resolution between Cuban independence ambitions and Spanish colonialism, was sunk in Havana harbor. After the U.S. naval victory led by Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish squadron at Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, the U.S. invited Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines, which he did on May 19, 1898, in the hope he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government. By the time U.S. land forces had arrived, the Filipinos had taken control of the entire island of Luzon, except for the walled city of Intramuros Manila, which they were besieging. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines in Kawit, Cavite, establishing the First Philippine Republic under Asia's first democratic constitution. Their dreams of independence were crushed when the Philippines were transferred from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1898), which closed the Spanish-American War.

Concurrently, a German squadron under Admiral Diedrichs arrived in Manila and declared that if the United States did not grab the Philippines as a colonial possession, Germany would. Since Spain and the U.S. ignored the Filipino representative, Felipe Agoncillo, during their negotiations in the Treaty of Paris, the Battle of Manila between Spain and the U.S. was alleged by some to be an attempt to exclude the Filipinos from the eventual occupation of Manila. Although there was substantial domestic opposition, the United States decided neither to return the Philippines to Spain, nor to allow Germany to take over the Philippines. Therefore, in addition to Guam and Puerto Rico, Spain was forced in the negotiations to hand over the Philippines to the U.S. in exchange for US$20,000,000.00, which the U.S. later claimed to be a "gift" from Spain. The first Philippine Republic rebelled against the U.S. occupation, resulting in the Philippine-American War (1899–1913).

Philippine-American War (1898 - 1946)

In Feb., 1899, Aguinaldo led a new revolt, this time against U.S. rule. Defeated on the battlefield, the Filipinos turned to guerrilla warfare, and their defeat became a mammoth project for the United States—

Thus began the Philippine-American War, one that cost far more money

and took far more lives than the Spanish-American War. Fighting broke

out on February 4, 1899, after two American privates on patrol killed

three Filipino soldiers in San Juan, Metro Manila. Some 126,000 American

soldiers would be committed to the conflict; 4,234 American and 16,000

Filipino soldiers, part of a nationwide guerrilla movement of

indeterminate numbers, died. Estimates on civilian deaths during the war range between 250,000 and 1,000,000, largely because of famine and disease. Atrocities were committed by both sides.

The poorly equipped Filipino troops were handily overpowered by American troops in open combat, but they were frightening opponents in guerrilla warfare. Malolos, the revolutionary capital, was captured on March 31, 1899. Aguinaldo and his government escaped, however, establishing a new capital at San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. Antonio Luna, Aguinaldo's most capable military commander, was murdered in June. With his best commander dead and his troops suffering continued defeats as American forces pushed into northern Luzon, Aguinaldo dissolved the regular army in November 1899 and ordered the establishment of decentralized guerrilla commands in each of several military zones. The general population, caught between Americans and rebels, suffered significantly.

The revolution was effectively ended with the capture (1901) of Aguinaldo by Gen. Frederick Funston at Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901 and was brought to Manila, but the question of Philippine independence remained a burning issue in the politics of both the United States and the islands. The matter was complex by the growing economic ties between the two countries. Although moderately little American capital was invested in island industries, U.S. trade bulked larger and larger until the Philippines became almost entirely dependent upon the American market. Free trade, established by an act of 1909, was expanded in 1913. Influenced of the uselessness of further resistance, he swore allegiance to the United States and issued a proclamation calling on his compatriots to lay down their arms, officially bringing an end to the war. However, sporadic insurgent resistance continued in various parts of the Philippines, especially in the Muslim south, until 1913.

The poorly equipped Filipino troops were handily overpowered by American troops in open combat, but they were frightening opponents in guerrilla warfare. Malolos, the revolutionary capital, was captured on March 31, 1899. Aguinaldo and his government escaped, however, establishing a new capital at San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. Antonio Luna, Aguinaldo's most capable military commander, was murdered in June. With his best commander dead and his troops suffering continued defeats as American forces pushed into northern Luzon, Aguinaldo dissolved the regular army in November 1899 and ordered the establishment of decentralized guerrilla commands in each of several military zones. The general population, caught between Americans and rebels, suffered significantly.

The revolution was effectively ended with the capture (1901) of Aguinaldo by Gen. Frederick Funston at Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901 and was brought to Manila, but the question of Philippine independence remained a burning issue in the politics of both the United States and the islands. The matter was complex by the growing economic ties between the two countries. Although moderately little American capital was invested in island industries, U.S. trade bulked larger and larger until the Philippines became almost entirely dependent upon the American market. Free trade, established by an act of 1909, was expanded in 1913. Influenced of the uselessness of further resistance, he swore allegiance to the United States and issued a proclamation calling on his compatriots to lay down their arms, officially bringing an end to the war. However, sporadic insurgent resistance continued in various parts of the Philippines, especially in the Muslim south, until 1913.

U.S. colony

Civil government was established by the Americans in 1901, with William Howard Taft as the first American Governor-General of the Philippines. English was declared the official language. Six hundred American teachers were imported aboard the USS Thomas. Also, the Catholic Church was disestablished, and a substantial amount of church land was purchased and redistributed. Some measures of Filipino self-rule were allowed, however. An elected Filipino legislature was established in 1907.

When Woodrow Wilson became U.S. President in 1913, there was a major change in official American policy concerning the Philippines. While the previous Republican administrations had predicted the Philippines as a perpetual American colony, the Wilson administration decided to start a process that would slowly lead to Philippine independence. U.S. administration of the Philippines was declared to be temporary and aimed to develop institutions that would permit and encourage the eventual establishment of a free and democratic government. Therefore, U.S. officials concentrated on the creation of such practical supports for democratic government as public education and a sound legal system. The Philippines were granted free trade status, with the U.S.

In 1916, the Philippine Autonomy Act, widely known as the Jones Law, was passed by the U.S. Congress. The law which served as the new organic act (or constitution) for the Philippines, stated in its preamble that the ultimate independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law placed executive power in the Governor General of the Philippines, appointed by the President of the United States, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature to replace the elected Philippine Assembly (lower house) and appointive Philippine Commission (upper house) previously in place. The Filipino House of Representatives would be purely elected, while the new Philippine Senate would have the majority of its members elected by senatorial district with senators representing non-Christian areas appointed by the Governor-General.

The 1920s saw alternating periods of cooperation and confrontation with American governors-general, depending on how intent the official who holds an office was on exercising his powers vis-à-vis the Philippine legislature. Members to the elected legislature lost no time in lobbying for immediate and complete independence from the United States. Several independence missions were sent to Washington, D.C. A civil service was formed and was regularly taken over by Filipinos, who had effectively gained control by the end of World War I.

When the Republicans regained power in 1921, the trend toward bringing Filipinos into the government was inverted. Gen. Leonard Wood, who was appointed governor-general, largely replaced Filipino activities with a semi military rule. However, the advent of the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s and the first aggressive moves by Japan in Asia (1931) shifted U.S. sentiment sharply toward the granting of immediate independence to the Philippines.

In 1934, the United States Congress, having originally passed the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act as a Philippine Independence Act over President Hoover's refusal, only to have the law rejected by the Philippine legislature, finally passed a new Philippine Independence Act, popularly known as the Tydings-McDuffie Act. The law provided for the granting of Philippine independence by 1946.

U.S. rule was accompanied by improvements in the education and health systems of the Philippines; school enrollment rates multiplied fivefold. By the 1930s, literacy rates had reached 50%. Several diseases were virtually eliminated. However, the Philippines remained economically backward. U.S. trade policies encouraged the export of cash crops and the importation of manufactured goods; little industrial development occurred. Meanwhile, landlessness became a serious problem in rural areas; peasants were often reduced to the status of serfs.

Commonwealth

The period 1935–1946 would ideally be dedicated to the final adjustments required for a peaceful transition to full independence, great latitude in autonomy being granted in the meantime.

The Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, passed by Congress in 1932, provided for complete independence of the islands in 1945 after 10 years of self-government under U.S. supervision. The bill had been drawn up with the aid of a commission from the Philippines, but Manuel L. Quezon, the leader of the leading Nationalist party, opposed it, partially because of its threat of American tariffs against Philippine products but principally because of the provisions leaving naval bases in U.S. hands. Under his influence, the Philippine legislature rejected the bill. The Tydings-McDuffie Independence Act (1934) closely looks like the Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, but struck the provisions for American bases and carried a promise of further study to correct “imperfections or inequalities.”

The Philippine legislature approved the bill; a constitution, approved by President Roosevelt (Mar., 1935) was accepted by the Philippine people in a vote by the electorate determining public opinion on a question of national importance (May); and Quezon was elected the first president (Sept.). On May 14, 1935, an election to fill the newly created office of President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines was won by Manuel L. Quezon (Nacionalista Party) and a Filipino government was formed on the basis of principles apparently similar to the US Constitution. (See: Philippine National Assembly). When Quezon was inaugurated on Nov. 15, 1935, the Commonwealth was formally established in 1935, featured a very strong executive, a unicameral National Assembly, and a Supreme Court composed entirely of Filipinos for the first time since 1901. The new government embarked on an ambitious agenda of establishing the basis for national defense, greater control over the economy, reforms in education, improvement of transport, the colonization of the island of Mindanao, and the promotion of local capital and industrialization. The Commonwealth however, was also faced with agrarian unrest, an uncertain diplomatic and military situation in South East Asia, and uncertainty about the level of United States commitment to the future Republic of the Philippines.

In 1939-40, the Philippine Constitution was revised to restore a bicameral Congress, and permit the reelection of President Quezon, previously restricted to a single, six-year term. Quezon was reelected in Nov., 1941. To develop defensive forces against possible aggression, Gen. Douglas MacArthur was brought to the islands as military adviser in 1935, and the following year he became field marshal of the Commonwealth army.

During the Commonwealth years, Philippines sent one elected Resident Commissioner to the United States House of Representatives, as Puerto Rico currently does today.

World War II and Japanese occupation

As many as 10,000 people died in the Bataan Death March.

War came unexpectedly

to the Philippines. Japan openned a surprise attack on the Philippines

on December 8, 1941, when Japan attacked without warning, just ten hours

after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Japanese troops attacked the islands in many places and launched a

pincer drive on Manila. Aerial bombardment was followed by landings of

ground troops in Luzon. The defending Philippine and United States

troops were under the command of General

Douglas MacArthur. Under the pressure of superior numbers, the

defending forces (about 80,000 troops, four fifths of them Filipinos)

withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay where they entrenched and tried to hold until the arrival of reinforcements, meanwhile guarding the entrance

to Manila Bay and denying that important harbor to the Japanese. But no

reinforcements were forthcoming. Manila, declared an open city to stop

its destruction, was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. The

Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of United

States-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on

Corregidor in May. Most of the 80,000 prisoners

of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake the

notorious Bataan Death March to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the

north. It is estimated that as many as 10,000 men died before reaching

their destination.

Quezon and Osmeña had accompanied the troops

to Corregidor and later left for the United States, where they set up a

government in exile. MacArthur was ordered out by President Roosevelt

and left for Australia on Mar. 11, where he started to plan for a

return to the Philippines; Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright assumed command.

The

besieged U.S.-Filipino army on Bataan finally fell down on Apr. 9,

1942. Wainwright fought on from Corregidor with a barracks of about

11,000 men; he was overwhelmed on May 6, 1942. After his surrender, the

Japanese forced the surrender of

all remaining defending units in the islands by threatening to use the

captured Bataan and Corregidor troops as hostages. Many individual

soldiers refused to surrender, however, and guerrilla resistance,

organized and coordinated by U.S. and Philippine army officers,

continued throughout the Japanese occupation.